Overview Exhibition /

Holon Design Museum

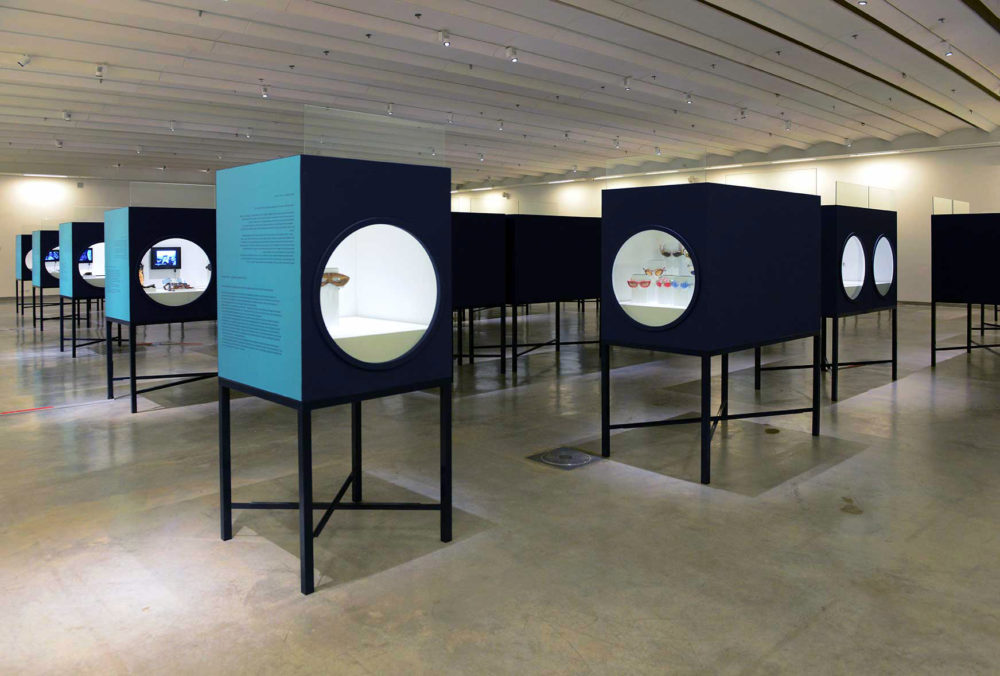

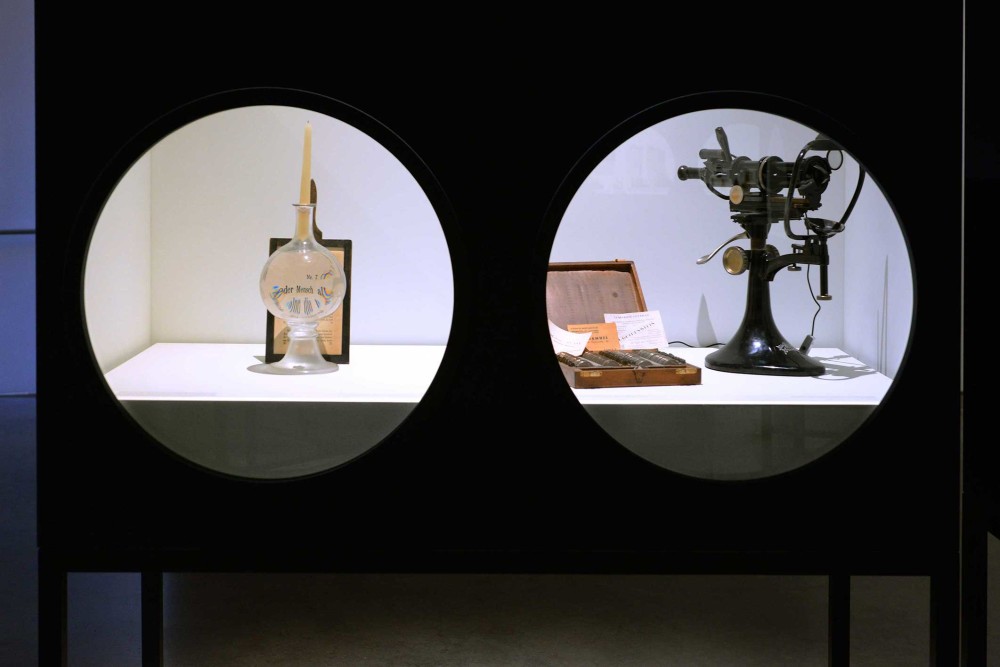

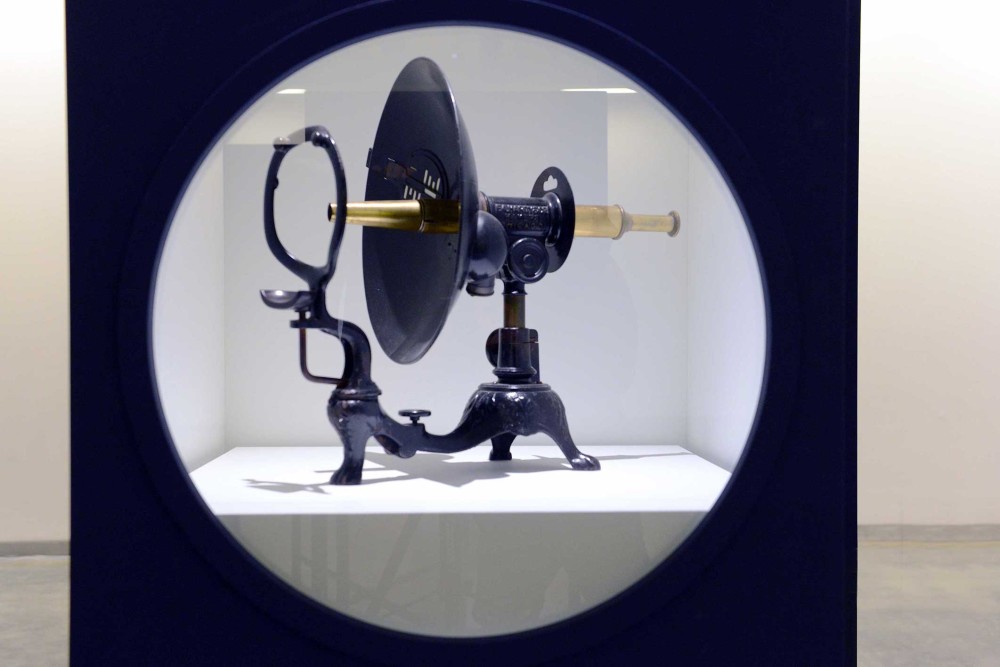

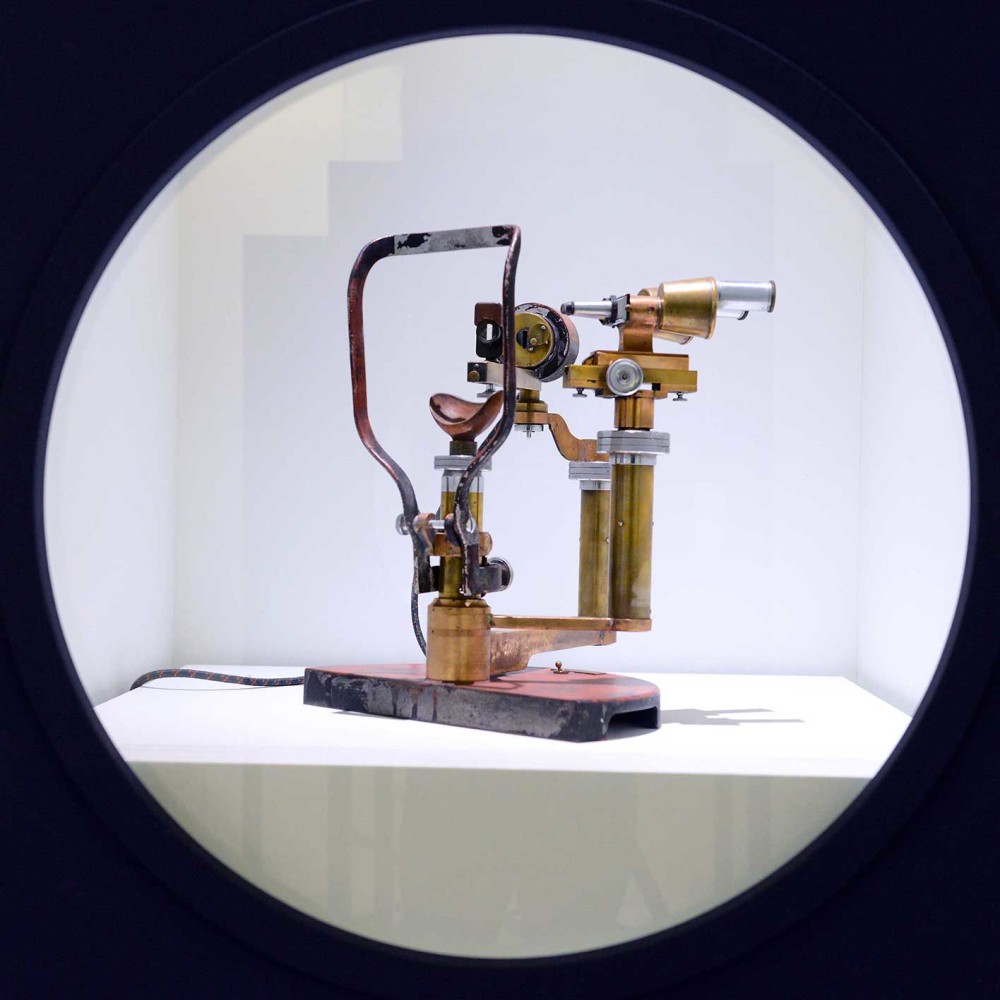

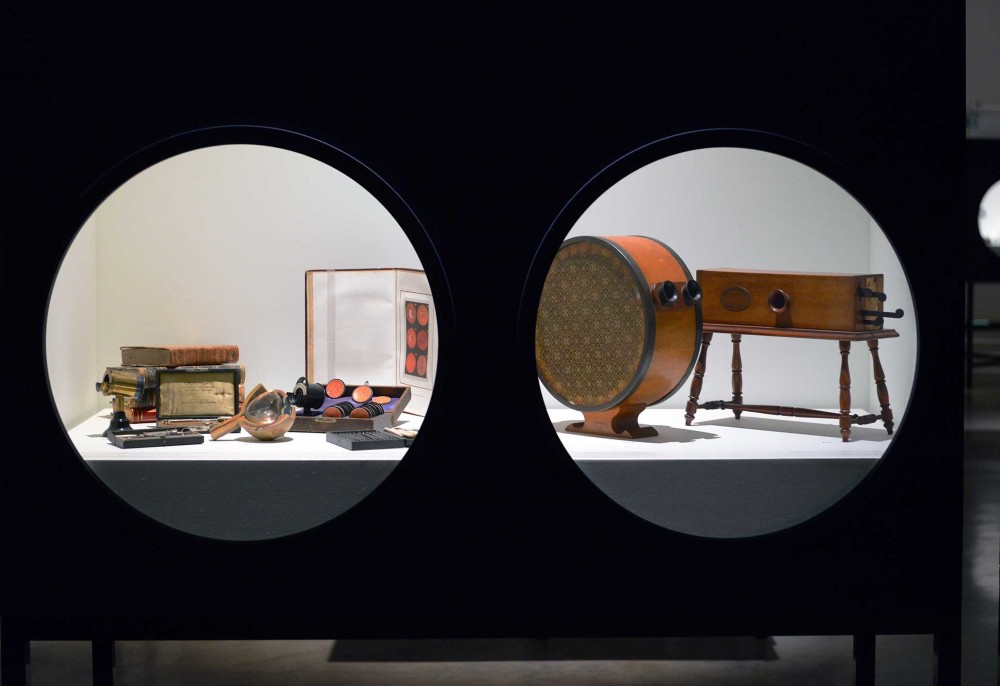

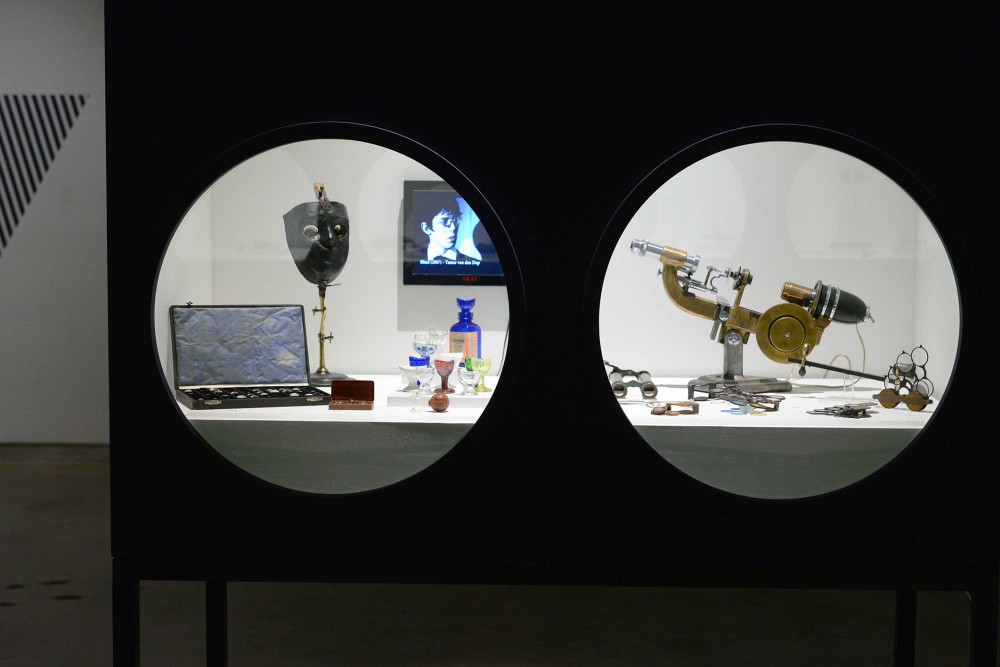

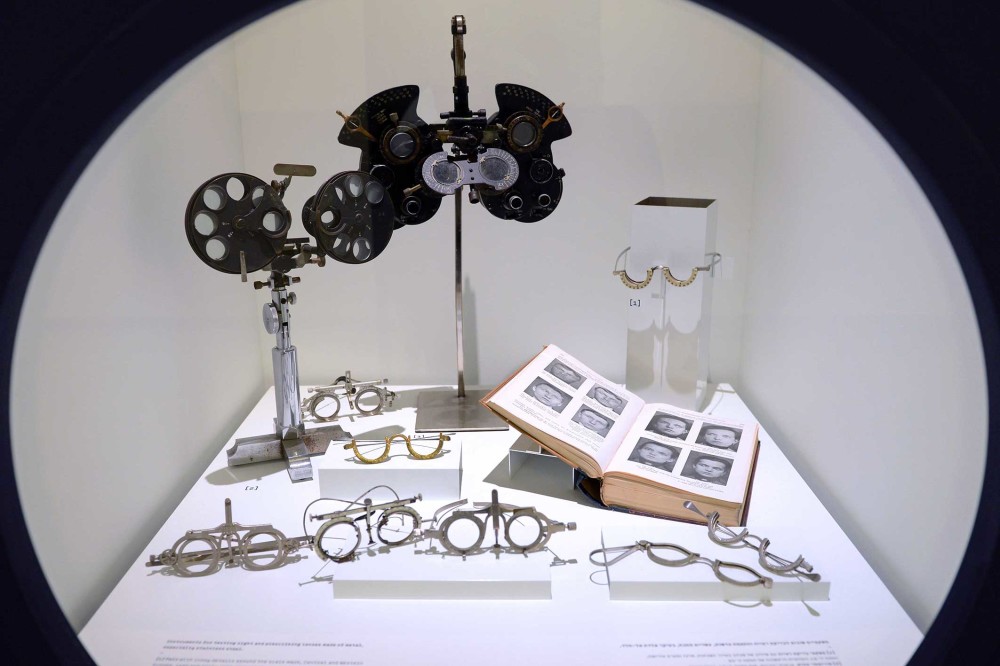

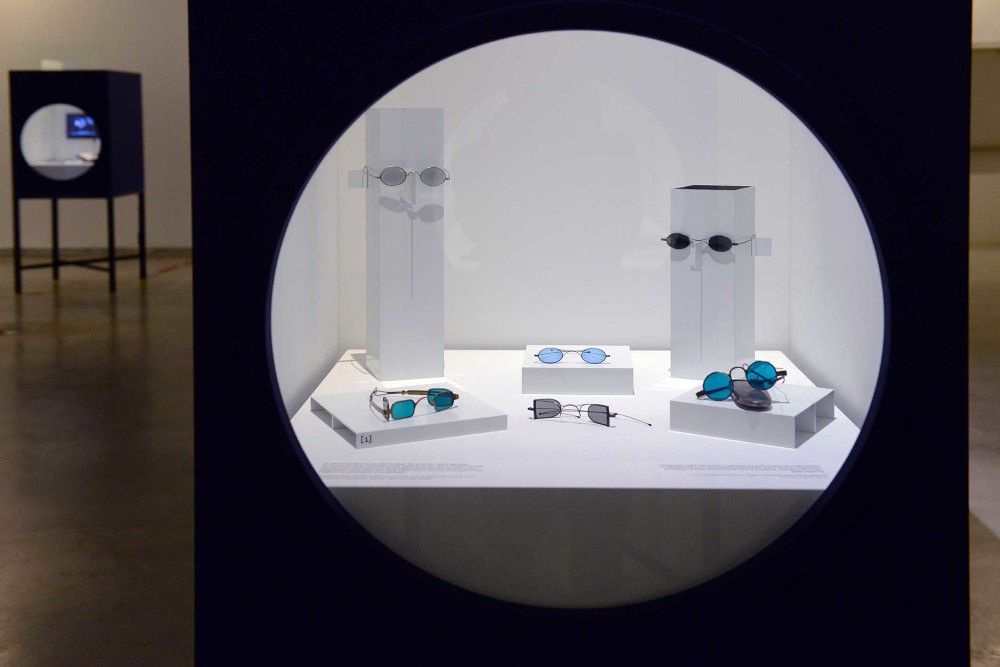

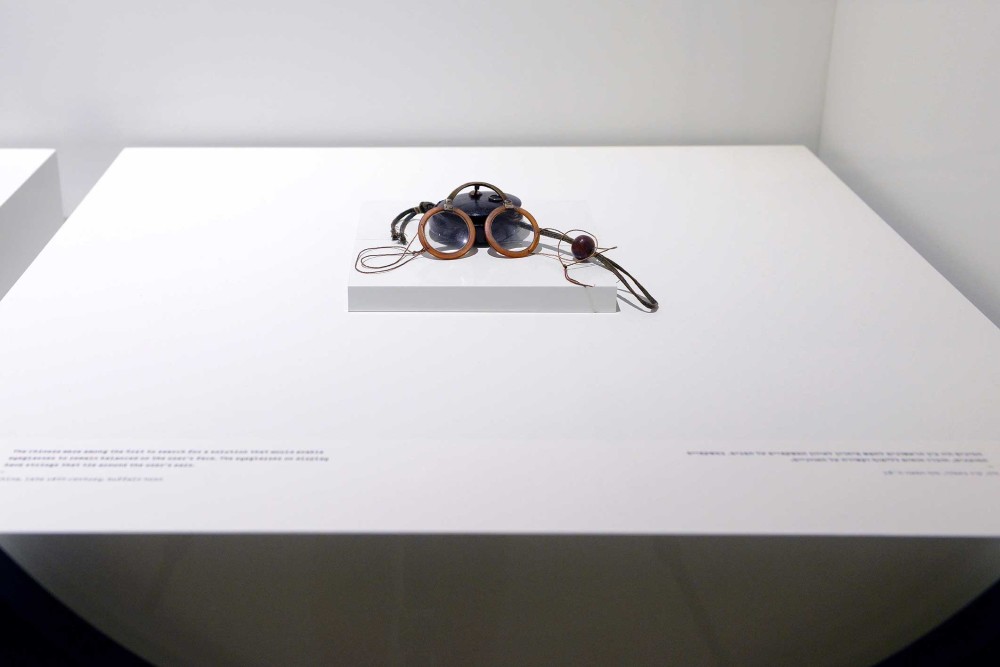

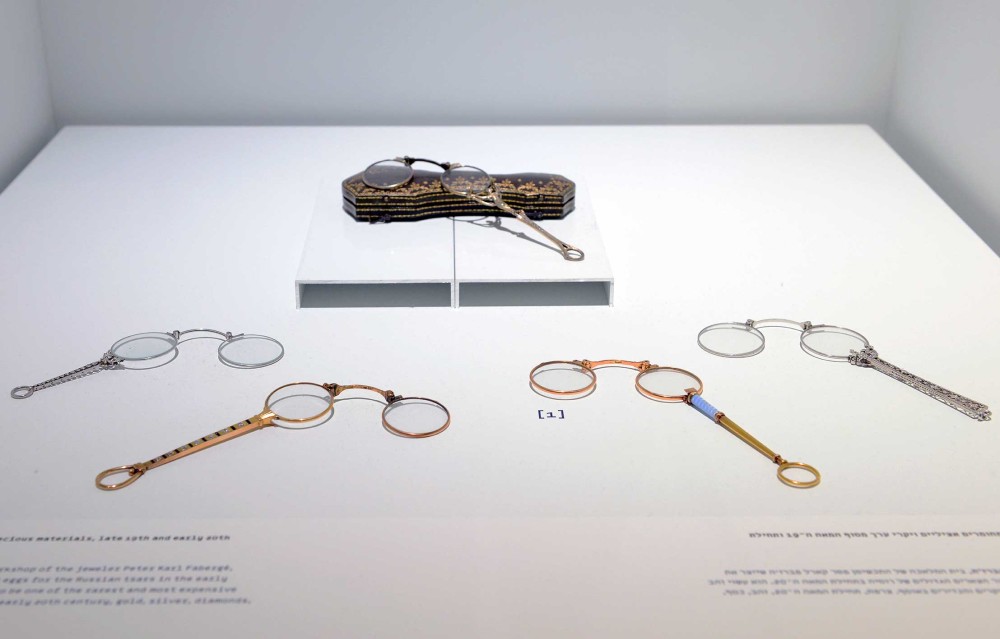

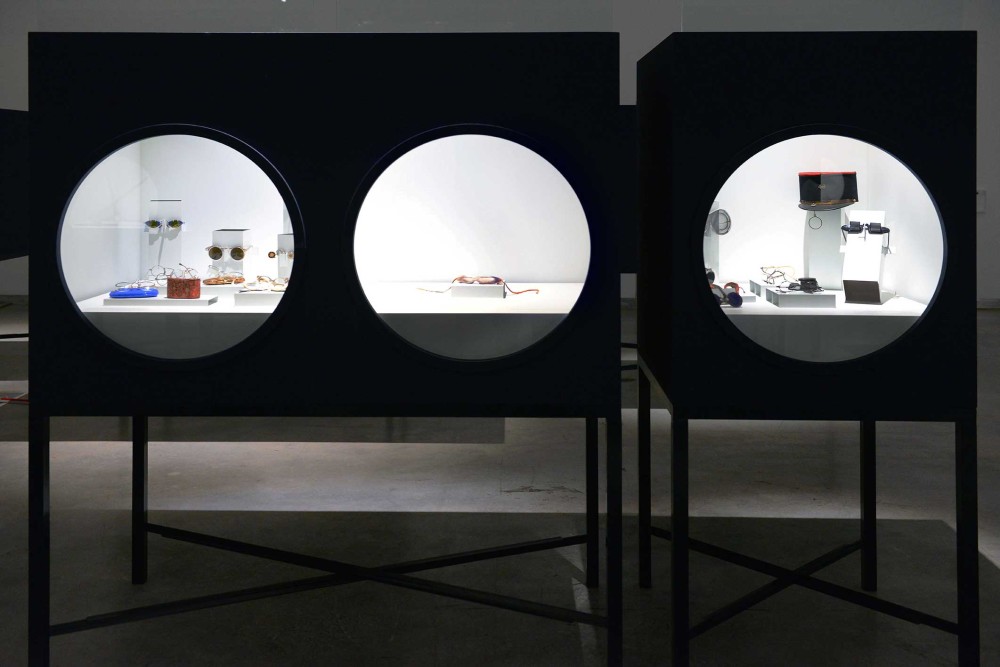

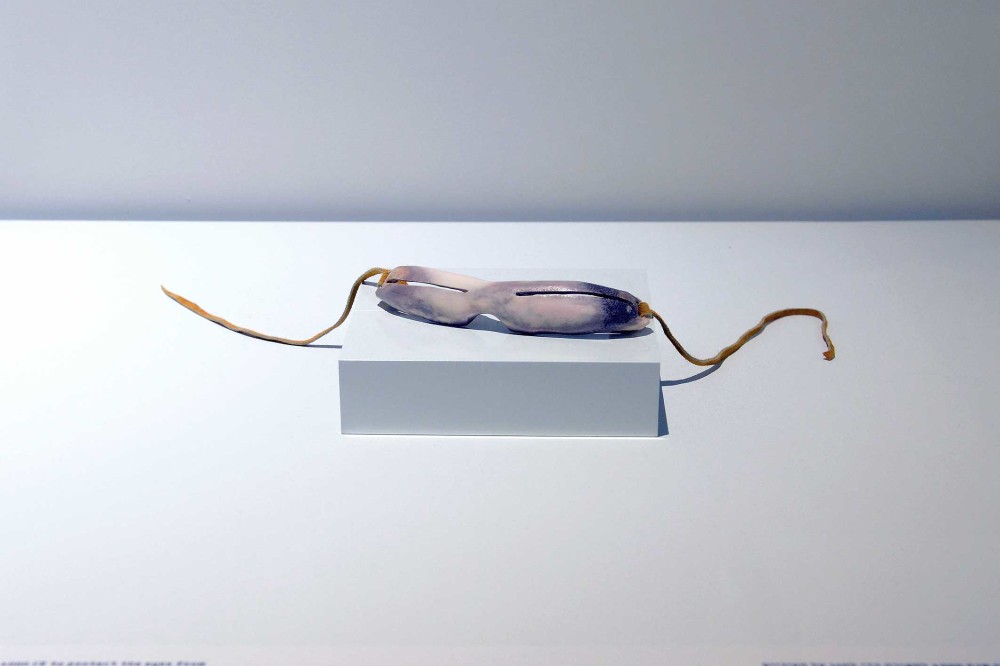

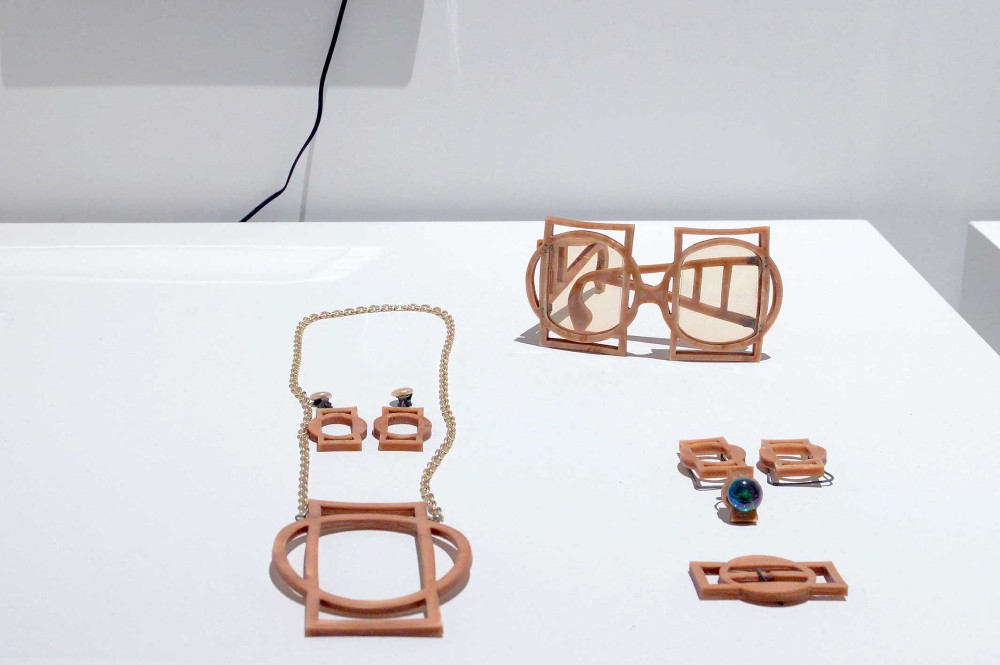

The exhibition Overview is the first exhibition in the world to display such an extensive collection of objects from the history of optic items. The 30,000 people who visited Design Museum Holon, one of the world’s most acclaimed design museums, between December 2016 and April 2017, were moved by the exhibition that presented only about a third of Claude Samuel’s collection. This site offers a virtual visit to the exhibition.

Curator:Maya Dvash

Exhibition Design: Tal Gur

Photography: Shay Ben Efraim, Alon Porat ,Eli Bohbot

*All the contents of the exhibition presented here (apart from the collectors text), including the categorization, were written by the exhibition curator and belong to the Holon Design Museum.

© All rights reserved to Design Museum Holon